By mid-1951 Ike was in Paris, hard at work laying the groundwork for a new military alliance destined to protect Western Europe from Soviet-advance. He was a grandfather, now 60 years old, and wanted nothing more than to complete his NATO mission, return to Columbia University, and — at some point — retire. Yet he was very worried for the future of his country in the uncertain atmosphere of the postwar era.

As early as 1943, Ike’s name had been casually linked with the highest office in the land. By 1948, public opinion polls indicated that he was America’s first choice for President of the United States. That same year, President Truman offered to run as his vice-president on an Eisenhower-Truman Democratic ticket. In the summer of 1949 and again in the fall of 1950, Governor Dewey of New York, approached Ike about a presidential bid. Ike made it clear: he was not interested.

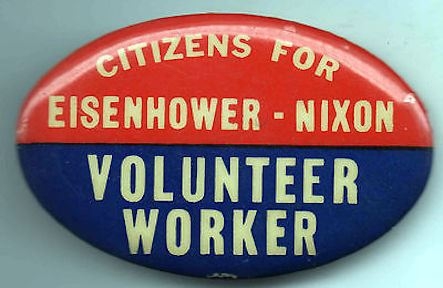

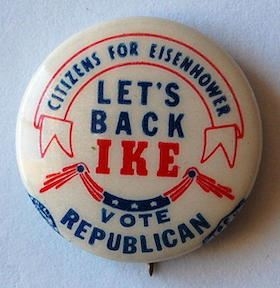

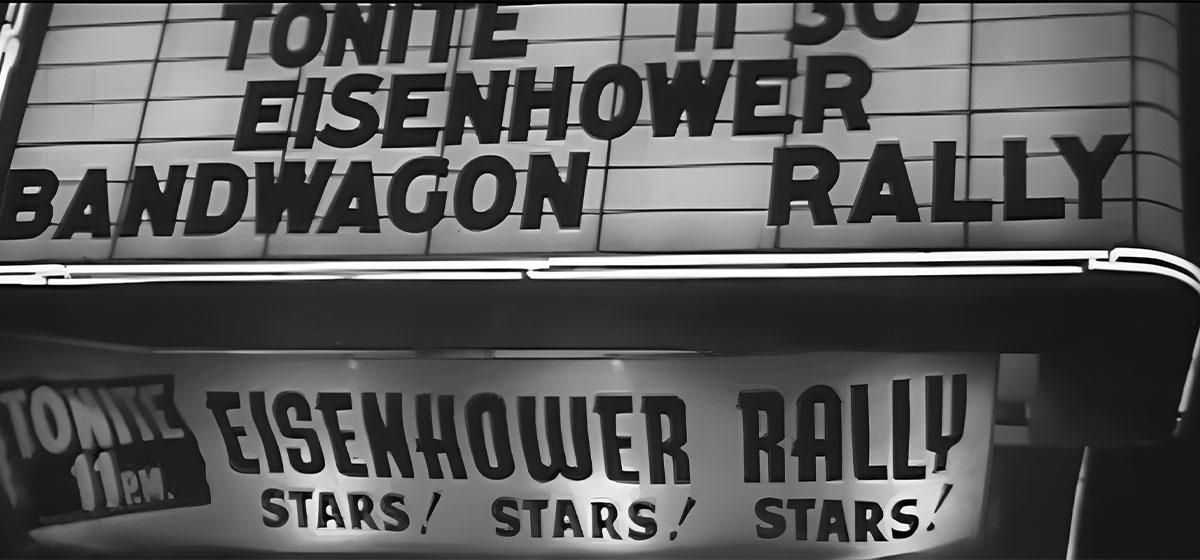

The “Eisenhower for President” campaign took shape in the summer of 1951. Ike’s closest friends and prominent Republicans worked behind the scenes to organize a campaign and raise money. Even earlier, grassroots volunteers began to organize under the umbrella of “Citizens for Eisenhower.” “Ike Clubs” sprouted across the country. There were “Volunteers for Eisenhower,” “Mothers’ Clubs for Ike,” and even “Democrats for Eisenhower.” One Los Angeles group took out a political ad declaring themselves “Democrats Anonymous for Ike,” adding, “May our ancestors forgive us — we’re going Republican.” Campaign buttons, clothing, banners, toys, stationery — all appeared emblazoned with “I Like Ike.”