For Dwight D. Eisenhower, the immediate postwar years were filled with change, new challenges, and frustrations. Throughout this entire period, the American people made it clear that they wanted Ike as their president, but he was yet to be convinced. Each time, as he prepared to retire, he was called back to service by his sense of duty.

From 1946-1948, Ike served as U.S. Army Chief of Staff before retiring from active duty. In 1948, he accepted the presidency of Columbia University. Then, once again, in 1950, President Truman asked him to return to active military service as the first military commander of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

When Ike became U.S. Army Chief of Staff in 1946, the Pentagon was newly constructed. It was an enormous place, interwoven with a maze of corridors that seemed to have no end. (In fact, Ike once became lost and had to ask directions back to his office; the incident made national headlines.) Immediately upon assuming this position, demobilization was his most pressing responsibility.

Ike’s next task was equally difficult — to reorganize the new postwar army. He believed that every 18-year-old male should serve one year of compulsory military service and that the regular peacetime army should be made up entirely of volunteers. To his great disappointment, neither idea was adopted.

Another postwar battle Ike fought and lost was the unification of the various branches of the armed forces. In the meantime — despite his impassioned arguments to the contrary — Congress slashed military budgets and greatly reduced the size of America’s postwar fighting force.

With disappointment and sadness, Ike observed the unfolding Cold War. He regretted the country’s growing reliance on nuclear weapons, but saw no realistic alternative. On one point he was absolutely certain — a restored and vital Europe was key to our own national security. Too much had been sacrificed to win the war only to allow Europe to collapse now.

As he prepared to retire, Ike was physically and mentally tired. He and Mamie dreamed of buying a ranch near a small college town where he could teach and write, but it was not to be. When he was approached, for a second time, to accept the position of president of Columbia University, Ike thought about the idea long and hard before saying, “Yes.” But first he had to schedule some time to write his memoirs of the war.

It had not been easy to convince Ike to write Crusade in Europe. There had been countless opportunities presented to him after the war, and he had turned them all down. To have served his country had been a great honor, and he refused to exploit it for personal gain. Finally, the argument that he had a duty to future generations to leave behind an accurate accounting of his experiences during the war convinced him to undertake the project.

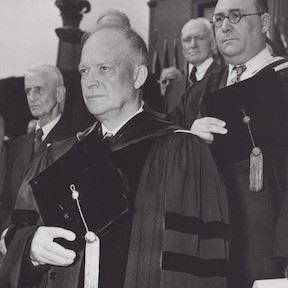

On October 12, 1948, in a ceremony befitting a head of state, Dwight D. Eisenhower was inaugurated as president of Columbia University. Characteristically, he threw himself into his new job, determined to learn everything be could about the university and its operation. At the request of President Truman, he agreed to provide much needed leadership to the new Department of Defense as well. The work was too much and on March 21, 1949, he collapsed with a severe attack of ileitis and was hospitalized. After a long recovery period, Ike was relieved to wrap up his work in Washington. He was eager to focus all his energies on his work at Columbia University.

In October, 1950, when President Truman summoned Ike to the White House it was because Ike was the unanimous choice of NATO members to lead its combined military force. Truman insisted that Ike was the only one who could make it work. Would he serve? As he prepared to leave for Europe, Ike offered to resign his position at Columbia. Instead, the Board of Trustees persuaded him to take an indefinite leave of absence.

Before leaving for his new post, Ike met privately with Senator Robert Taft of Ohio, hoping to convince him to support NATO. But the meeting ended without any commitments. As Ike assumed his duties in Paris in January 1951, the threat of a Soviet attack on Western Europe seemed imminent. Ike believed that if western civilization was to survive, NATO, especially its military force, must succeed. Back home, however, sentiments for postwar isolationism were gaining momentum.

The Eisenhower Family

The Eisenhower’s personal lives were also undergoing transition. Ike now led a very public life, surrounded by a staff and personal aides who catered to him. Mamie regretted the the war had hardened her husband. She noted that he was more abrupt and impatient and overly serious. On her part, Mamie had become far more independent in Ike’s absence. Each found the changes in the other unfamiliar and uncomfortable. It would take time and patience to become a close couple again.

In September 1946, while Ike was Chief of Staff, word arrived that his mother, Ida Stover Eisenhower, had died peacefully at age 84. Ida’s death was a devastating blow. All five Eisenhower brothers returned home to Abilene for her funeral. Then, in the summer of 1951, while the Eisenhower were living in France, John Sheldon Doud, Mamie’s beloved “Pupah” died.

After World War II, son John remained on duty in Germany and, in early 1946, was reassigned to Vienna. It was there, in late October 1946, that he met Barbara Jean Thompson, daughter of an army colonel. On June 10, 1947, John and Barbara were married in a ceremony befitting the son of the Chief of Staff. Dwight David Eisenhower II was born in 1948; Barbara Anne arrived one year later. (Eventually there would be four children.) Now in their 50s, Ike and Mamie were thrilled to become grandparents and would develop close relationships with their grandchildren.

In 1948, while the Eisenhower were at Columbia University, Thomas E. Stephens painted a portrait of Mamie. Ike watched in total fascination. When Stephens finished, Ike himself tried painting. From then on, he rarely missed an opportunity to paint, usually in the late hours of the night. Painting, along with reading westerns and playing golf, allowed him to escape momentarily the ever-present stresses of his life.

After the war, the Eisenhower never again lived in “ordinary” housing. Their homes were official residences where they were expected to entertain. While Ike was Chief of Staff, they lived in stately Quarters #1 at Fort Meyer. Sixty Morningside Drive, their official Columbia University residence, was a four-story mansion of marble and brick. While at Columbia, the Eisenhowers bought their first home, near Gettysburg. Here they would retire. Their NATO residence was a newly renovated 14-room villa outside Paris.

Throughout the period 1945-1951, Mamie shared the limelight with her famous husband, and everything about her was scrutinized. She had always loved clothes and had developed her own sense of style. Mamie Eisenhower was no “fashion snob,” however. She was equally at ease in a dress straight off the rack from J.C. Penney’s as in a designer gown. When letters and articles suggested that she should try a new hairstyle — minus her trademark bangs — she paid little attention. Mamie liked how she looked and had no intention of changing.

This content is from The Eisenhower Life Series: In the High Cause of Human Freedom, an educational series written by Kim Barbieri for the Eisenhower Foundation, copyright 2002. Funding was provided by the Dane G. Hansen Foundation and the State of Kansas.

For a complete timeline of Dwight D. Eisenhower's life, visit the Eisenhower Interactive Timeline.

Eisenhower Foundation

Eisenhower Foundation