". . . War brings about strange, sometimes ridiculous situations. In my service I've often thought or dreamed of commands of various types that I might one day hold -- war commands, etc. One I now know could never, under any conditions, have entered my mind even fleetingly. I have operational command of Gibraltar. The symbol of the solidity of the British Empire -- the hallmark of safety and security at home -- the jealously guarded rock that has played a tremendous part in the trade development of the English race! An Americana is in charge and I am he." - DDE, November, 1942

Five days after the disaster at Pearl Harbor, on December 12, 1941, Ike answered a phone call from Washington. “The Chief,” United States Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall, wanted him in Washington right away. Ike’s heart sank; what he had feared all along — a desk job in Washington, D.C. rather than a combat command — was to be his wartime duty.

When Ike arrived, General Marshall summarized the situation in the Pacific and asked, “What should be our general line of action?” Momentarily taken aback, Ike asked for time and a desk. Several hours later, he emerged with a plan and handed it to Marshall, who read through it silently, without expression. Finally, he responded, “I agree with you.”

Ike spent an intense six months in the War Department. His first assignment made him Deputy Chief in charge of Pacific Defenses. In February 1942, he was promoted to Chief of the War Plans Division, and in March, Marshall named him the Assistant Chief of Staff in charge of the newly formed Operations Division. At the time, Ike could not have imagined that within eight months he would be en route to his first combat command at age 52.

General Dwight D. Eisenhower & Brigadier General Leonard Gerow, Washington, DC. January, 1942.

Along with the new responsibilities came promotions. That spring, on the recommendation of General Marshall, Ike received a second star, making him a major general, and, in July, he was awarded a third. These were temporary wartime promotions, however; in the world of the regular army, he remained Colonel Eisenhower.

In those first days of 1942, the atmosphere at the War Department was heady with a sense of urgency and purpose. Ike’s workload was crushing, never letting up. He was at his desk sixteen hours a day, seven days a seek, gulping down quick meals while he worked. His health suffered with frequent minor illnesses. Despite the stress and fatigue, Ike’s performance was exceptional in every respect. In Eisenhower, Marshall recognized a superior officer who consistently performed far beyond what was asked of him. He was a natural leader and the consummate professional, passing every test that Marshall put in front of him.

In late May 1942, Ike traveled to London to iron out difficulties between the War Department and the American headquarters in London. Shortly after, he was named the new American commander of the European Theater of Operations. On June 24, he returned to London to begin the process of creating an Anglo-American Alliance — an unprecedented and daunting task.

Ike’s job of welding together the alliance was possibly the most formidable task of the war. American and British officers and troops would have to overcome cultural and military differences to win the war. He first organized the Allied command structure, ensuring that every American officer answered to a British officer and vice versa. He walked a fine line to avoid being labeled as “pro-British” by the Americans and “pro-American” by the British. By May 1943, when hard-won Tunis finally fell to the Allies, it was apparent that the American Allied Commander had accomplished the nearly impossible. It had been an exhausting task.

during a conference in London. September 29, 1942.

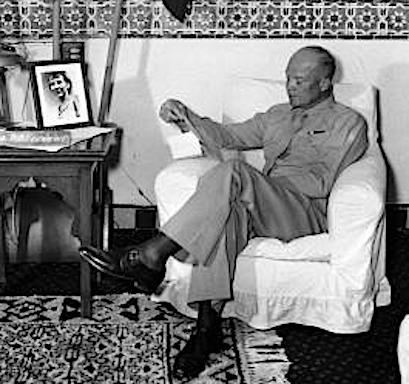

For those under his command, Ike cultivated an image of calm and dignity, free from stress, worry, and self-doubt. Instinctively, he understood that subordinates looked to their leaders to cue their own optimism and enthusiasm. As an example to everyone else, he worked incessantly; there was just too much to do to pause or let down. In North Africa, Marshall was so alarmed by Ike’s exhausted appearance that he ordered him to slow down, delegate more, and rest or he would not survive the war.

As the Allies engaged the Axis Powers in North Africa, Ike remained blissfully unaware of his growing celebrity. In the autumn of 1943, the first “Ike-for-President” movement appeared. With a war yet to be waged and won, he was not flattered or pleased. Isolated from the home front and consumed by his work, he had little time or inclination to consider how his life would be affected by his leadership in World War II.

Allied victory was secured in North Africa on May 15, 1943, with the fall of Tunisia. By August 16, the surrender of Sicily was complete, clearing the path for the invasion of Italy. The fighting there was half-hearted and sporadic until October 4, when Hitler finally made the decision to fight for Italy. However, Ike would have no choice but to leave the Italian campaign to other commanders. On December 7, 1943, two years to the day after the attack on Pearl Harbor, he was summoned by President Roosevelt. To his astonishment, the President said, “Well, Ike, you are to command Overlord.”

As did many American families during World War II, the Eisenhowers had to adjust to separation and a state of uncertainty. Son John was in his plebe year at West Point when his father was called to the War Department following Pearl Harbor. In February 1942, Mamie joined Ike in Washington where they moved into the Wardman Park Hotel.

On March 10, Ike received word that his father, David, had died at age 79, but there was no time for the luxury of grief. The nation was at war, and it was simply impossible for Ike to leave his job to travel back to Abilene to attend his father’s funeral. Ike’s younger brother Roy died unexpectedly on June 17.

On the weekend before Ike’s departure for London on June 23, 1942, the Eisenhowers said their good-byes to one another. Ike and Mamie would not see each other for a year and a half. As John walked down the sidewalk, he turned and saluted his father, who returned the salute. Mamie could bear it no longer and burst into tears.

“Mrs. Ike,” as General Eisenhower often referred to his wife, remained in the background as much as she could while her husband was in London and North Africa. By June 1943, however, Ike’s celebrity was affecting her too. She was inundated with invitations and requests for interviews, and she could not begin to keep up with the mail. Mamie did not sit at home; she kept busy with wartime volunteer activities and worked hard to be a model of calm and strength for others. Newspaper and magazine articles written at that time about Mamie described her as poised, charming, and warm.

Mamie and Ike had enjoyed a close marriage for more than 25 years and were miserable apart. They wrote letters to each other throughout the war. His letters to her were written in longhand and are testaments to his love for her and the hope that she would not forget him. Military secrecy prevented him from telling her much about his day-to-day life.

John’s life at West Point was also affected by the war. Graduation dates were moved up one year, and cadets were sent to regular army camps to train instead of the usual summer camp. As might be expected, cadets were impatient with being treated like children when there was a war on. Young men their age were already facing the enemy!

Ike’s enormous fame changed John’s life much as it did Mamie’s. He was now, first and foremost, the “son” of a famous father. This “reflected prominence,” as he called it, had both benefits and liabilities. At West Point, it was not as noticeable, but once he graduated, it was clear that people treated him differently just because he was Ike’s son.

John was at home with his mother for Christmas in 1943 when the news came over the radio that his father had been appointed the Supreme Commander for the Allied invasion of Europe. The hall leading to the Eisenhowers’ suite was flooded with reporters. Life was changing quickly for the Eisenhower family. Mamie and John would now have to share Ike with an adoring public of millions, and their private lives would never be the same again.

Headquarters at the Hotel St. George. Algiers, North Africa. 1943

This content is from The Eisenhower Life Series: In the High Cause of Human Freedom, an educational series written by Kim Barbieri for the Eisenhower Foundation, copyright 2002. Funding was provided by the Dane G. Hansen Foundation and the State of Kansas.

For a complete timeline of Dwight D. Eisenhower's life, visit the Eisenhower Interactive Timeline.

Eisenhower Foundation

Eisenhower Foundation